End of Growth & Collapse

The belief that we can keep growing endlessly on a planet with limited resources is fundamentally flawed and unsustainable.

Can the economy keep growing forever? No, of course not. It's a complicated topic, even though the FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) crowd often makes it sound super straightforward. I’m not an economist by profession, but I do have a B.Sc. and M.Sc. in Economics, with a major in Financial Economics, so I understand how financial markets work and the assumptions behind asset pricing models.

One of the big ideas in the FIRE movement is the 4% rule. Basically, it assumes your investments will earn, for example 7% on average every year, and you withdraw 4% each year to live on. So, if you need $100,000 annually, you would need: $100,000 / 4% = $2.5 million. Once you’ve got $2.5 million invested, you can supposedly retire comfortably, pulling out $100,000 a year (and that amount would grow over time as your principal keeps growing). Sounds simple, right?

Here are some “historical” rates:

The S&P 500 has had an annual return of 6-7% after adjusting for inflation since its inception.

The average annual real global GDP growth rate (inflation adjusted) over the past 70 years is approximately 3.15%.

Here are some other important numbers to keep in mind and which I will discuss later in more detail:

The average annual increase in global energy consumption over the past 70 years is 2.75%. *Note how this is almost the same as GDP growth.

On average, the global population has increased by 1.5% per year over the past 70 years. The population growth rate peaked a long time ago, however we are still adding 80 million per year, a lot of new consumers.

Historical Stock Market Returns

This chart shows the S&P 500, and its predecessors, since around 1910 (logarithmic scale). You can see our history in this chart; the Great Depression of 1929, World War 2, 1970’s oil crisis, the Dot-com bubble of 2000, the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

To most people, this chart seems perfectly normal – just a sign of human progress and ingenuity, with a few bumps along the way. Many would assume that it will keep growing, as long as we have the right policies and continue innovating. After all, it's built on a strong 100-year track record, right?

What fueled economic growth in the past?

There are many variables to consider, but I believe the following are the fundamental drivers of past economic growth:

Growing population (1.4% per year): A growing population means increased demand and consumption, ranging from basics such as food, water, housing, clothing, energy, and healthcare, to non-essentials such as transportation, appliances, electronics, travel, entertainment. Every human being requires resources. Some much more than others. Without consumption, there is no economy.

Abundant natural resources and raw materials: Every product is made from something, often a combination of materials; metal ores, non-metallic minerals, biomass, fossil fuels, plastics, salt, sand, timber, soil, rubber, fresh water, rare earth elements, fish and seafood and so on. We have been extracting and depleting raw materials and natural resources faster than they can replenish, converting them to products (wealth) at an ever increasing rate.

Abundant and cheap energy: None of our growth would’ve happened without energy. Cheap fossil fuels kicked off the Industrial Revolution and have been driving our growth ever since.

Everything we do needs energy. We need food to power our bodies, and all movement, physical and economic, requires energy.

Fossil fuels are ancient solar energy stored up over millions of years, meaning they’re a one-time deal on human timescales.

The price we pay is just for extracting them (and even that’s not really priced right). They’re finite, and using them comes with major externalities, such as climate change from CO2 emissions.

Technological innovation: Technological innovation has brought some major changes:

It’s fueled population growth through medical breakthroughs like vaccines and penicillin, and boosted food production through fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

It’s made us way more productive through machinery and automation, ramping up industrial output.

It’s also created whole new industries, such as cars, air travel and tourism, TVs, computers, phones, video games, and more.

All these factors have driven the exponential economic growth we’ve seen over the past 200 years. Things really took off after the 1950s, but the stage was set a long time ago. So, can we keep growing at 2-3% per year forever, like many economists at the IMF, World Bank, and governments seem to think? No way.

Understanding exponential growth

Let’s break down linear vs. exponential growth with a simple example. Say you start with $100. With linear growth, you add the same amount, let’s say $10, every year. So after 10 years, you’d have $190, and after 50 years, you’d have $590. After 100 years, you’d get to $1,090.

Now, let’s look at exponential growth. If you grow by 10% each year, you’d have $110 after year 2, $121 by year 3, and around $259 at year 10. After that it gets wild: after 50 years, you’d have over $11,700, and after 100 years, a mind-blowing $13.8 million. Linear growth adds up slowly, but exponential growth snowballs into something massive over time.

A 2.5% growth rate per year means the economy would double every 28 years. If global GDP (currently at $110 trillion) grows at 2.5%, it would be $220 trillion by 2050, $356 trillion by 2075, and $724 trillion by 2100, adjusted for inflation. By then, we’d be consuming seven times more per year than we do now.

If this growth keeps going, by 2200 we would be consuming 19 times more, with a GDP of $1.9 quadrillion. By 2300, we’d be at 52 times more, with a GDP of $5.2 quadrillion. Considering that we’re already using more resources than the planet can handle, it’s pretty clear that exponential growth cannot continue for long.

I don’t think anyone realistically expects this kind of growth to play out, and most people aren’t even thinking about the year 2100, let alone beyond that. But still, perpetual growth seems to be the goal for a lot of political leaders, and it’s a core assumption in the models used to value financial assets, plan pension systems, and structure society. Our debt-based economic system demands continuous growth, because debt needs to be paid back with interest, and for that to happen, the economy needs to keep expanding.

Let’s take a closer look at the basic asset pricing models that most economists learn about.

Asset Pricing Model assumptions

Asset valuation models, like Discounted Cash Flow model (DCF) and Dividend Discount Model (DDM) are based on the idea of endless growth, which just doesn’t hold up when you look at the real world. If we plug in more realistic assumptions, the whole thing falls apart.

Take McDonald's, for example: if we assume 3.2% growth forever, the stock is worth about $315 per share with DCF and $164 with DDM. But if we assume no growth at all, those values drop to $166 and $87.

Input assumptions:

Free cash flow (FCF): $8.5 billion

Annual dividend: $6.07

Discount rate: 7% (cost of capital i.e. interest rates)

Growth rate:

3.2% in perpetuity

No growth

Results from running the models:

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Model:

With 3.19% growth: $315.36 per share (close to current price)

With 0% growth: $166.34 per share.

Dividend Discount Model (DDM):

With 3.19% growth: $164.40 per share.

With 0% growth: $86.71 per share.

If we factor in a 2% annual decline in revenue, the stock’s value drops even more to around $127 (DCF) or $66 (DDM).

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF):

Fair Value: $126.79 per share.

Dividend Discount Model (DDM):

Fair Value: $66.10 per share.

McDonalds stock is priced as if growth of 3% will continue into the far future. This applies to nearly all financial assets.

Obviously this isn’t just about McDonald's. Companies and sectors have always gone through boom-and-bust cycles, what’s different now is the risk of a shrinking population and resource shortages affecting the underlying assumptions at the macro-level.

The real issue is that our whole economy is built on the idea that growth will never stop, sort of like a big Ponzi scheme, it only works when it’s growing. If that growth stalls, things could get ugly fast.

A stock market crash won’t just hurt investors, it will hit everyone. First, those who rely on fixed incomes, such as pensioners, retirees, and people depending on investment returns. These groups spend a significant portion of their money on goods and services, and if their savings are reduced, their consumption will decline. This drop in consumption would create a ripple effect throughout the entire economy. Without growth, the whole system will implode.

I'm not saying that we should try to save the stock market or keep pushing for growth. What I'm pointing out is that this current system is not sustainable, and things that are unsustainable will eventually fail.

Money, interest and debt

As we have already established, our economic system is built on growth. Without it, debts can’t be paid, and things can quickly spiral downhill.

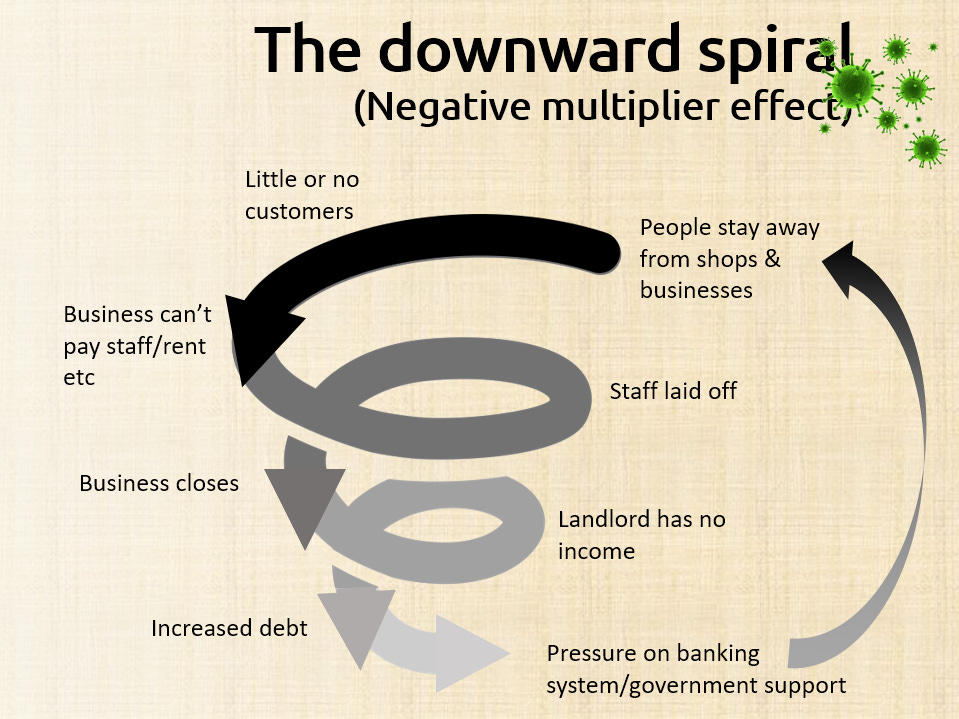

When the economy shrinks, people have less money to spend, or their money doesn’t go as far due to inflation. This leads to businesses having lower sales, forced to cut jobs, and the government’s services and welfare systems get more pressure. As unemployment rises, consumption drops even more, and the cycle continues with more layoffs and bankruptcies. We’ve seen recessions play out many times.

Money is essentially created as debt. When you take out a loan, the bank creates new money, and adds it to your account. But the interest is not created. So the interest has to come from somewhere. On the aggregate, this interest needs to be covered by economic growth, converting resources into products. We’re locked into a system that requires constant growth to pay off debt, and there’s never enough money in the system to cover all the debt that’s out there.

If growth slows down, we’re stuck with two choices: take on more debt to cover the old debt (kick the can down the down), or risk a recession and a deeper economic depression. Neither option is great, but politicians tend to choose taking on more debt, hoping for some kind of miracle.

Governments rely on taxes to fund services. These days, tax revenues often don’t cover expenses, so they run a deficit (borrow money). They assume (or hope) that the economy will grow enough to cover both the debt and interest. But if the economy doesn’t grow enough, they can’t pay back the debt and the interest payments will be an even larger part of their expenses.

When populations inevitably start to decline, tax revenues will drop even further, forcing governments to juggle lower income (tax revenues) and higher interest payments. When a country’s GDP falls, its debt doesn’t shrink; the debt stays the same. If you lose your job and have to take a lower paying job, your mortgage payments are still the same as they were before.

The reality is, we’ll never pay off all this global debt, and that’s not really the plan anyway. It’s a bit like musical chairs, eventually countries will hit a point where their debt-to-GDP ratio becomes completely unsustainable, and the interest payments eat up so much of their budgets that they can’t keep servicing the debt.

When governments borrow money (like when the US sells treasuries), the debt gets bought by investors such as:

Individual investors

Institutional investors

Foreign governments

Central banks

Commercial banks

Hedge funds and asset managers

Corporations

But what happens when investors stop believing the economy can actually grow enough to repay the debt? They lose faith in the system? Or they think the end of the world is near? They’ll demand a higher yield or simply not buy treasuries. And when that happens (this has already partially happened), who will buy the debt?

Central banks can always print more money and buy the debt, which increases the money supply without adding goods to the economy. This leads to inflation, and it’s a temporary fix, kicking the can down the road for future administrations to deal with.

On one hand, we need growth to keep society functioning the way it does now, but on the other hand, unlimited growth isn’t going to happen. Something’s got to give.

Let’s look at the factors that have driven growth so far and what the future trends look like for those growth drivers.

Global GDP

Like we talked about earlier, the average real GDP growth rate over the past 70 years has been around 3.15%. While growth has slowed down a bit, most countries, governments, and economists are still counting on (or hoping for) at least 2% growth going forward. They are taking on 30-year debt with interest at 4.44% to try and boost the economy today. That’s not going to end well.

GDP is often framed as a measure of production, but it’s really about consumption. GDP is clearly on an exponential trajectory. For that growth to continue there needs to be more consumers (endless population growth) and more stuff to consume (unlimited resources).

Population growth

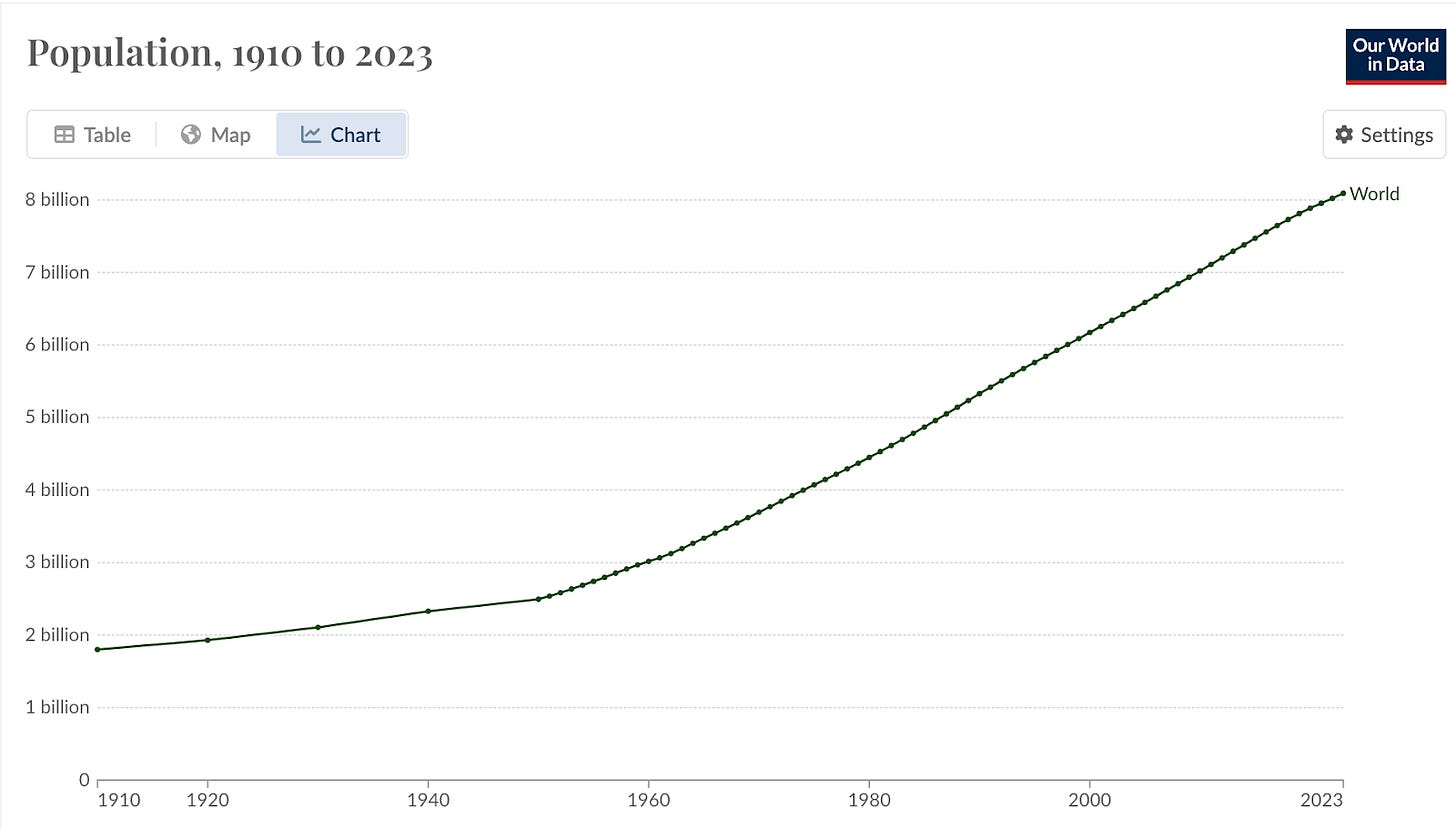

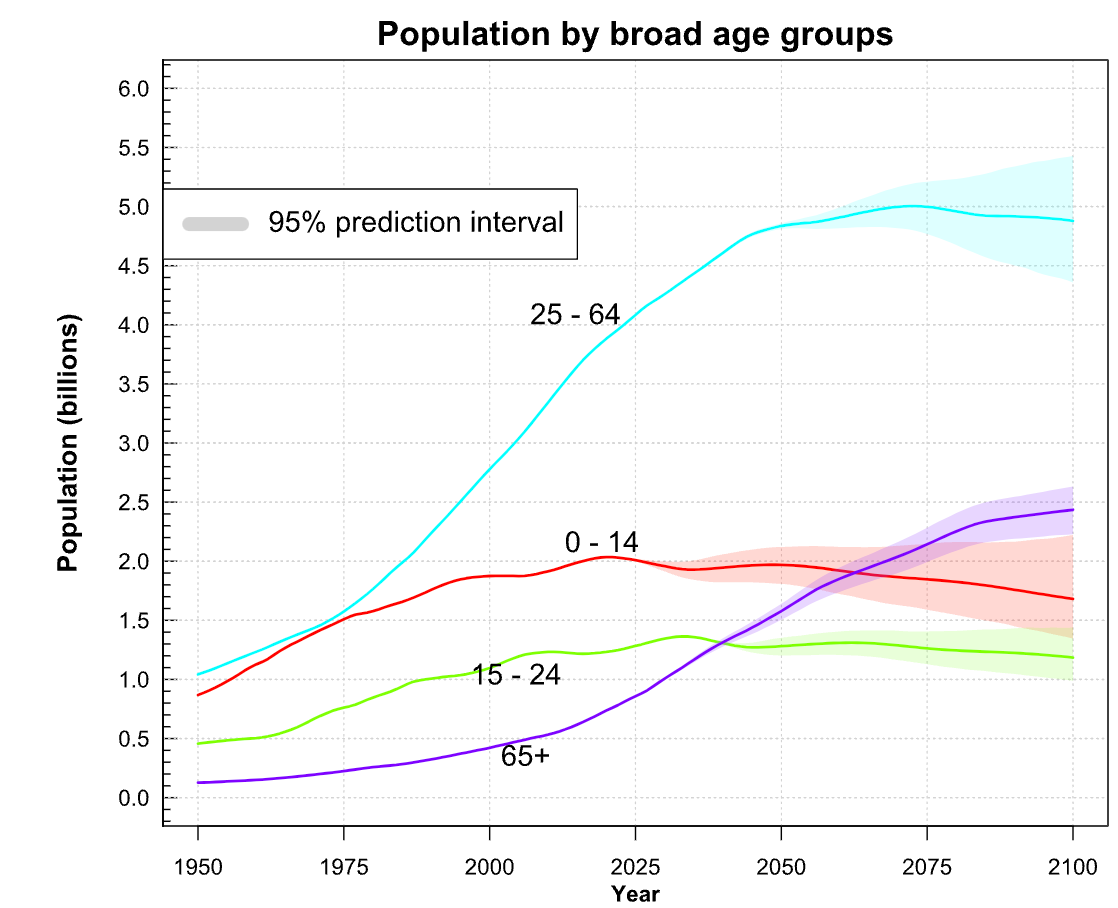

The chart below shows world population growth over the last century. This is the time period that asset pricing models assume is “normal” and use to predict future growth. The world population has grown from 2 billion to 8 billion, that’s a lot of new consumers driving up overall consumption.

Let’s zoom out to see if this is “normal” and if the current trajectory is sustainable:

The last 150 years are anything but normal and this trend clearly cannot keep going. It’s impossible. So, where’s the population headed?

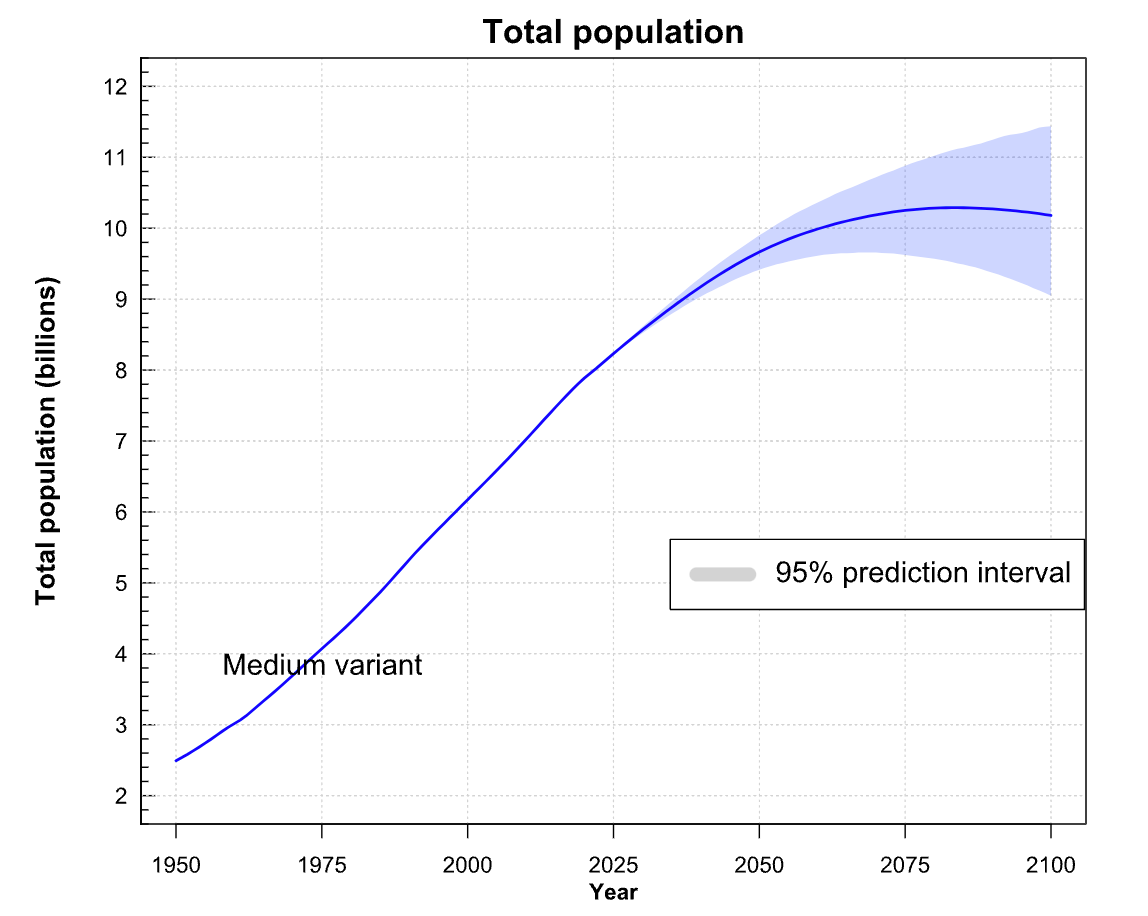

Fertility rates are dropping in almost every country, and most developed nations are well below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman. There's no sign this trend will change anytime soon, in fact, it’s dropping faster than ever. This is a clear sign that our population will peak soon. We won't hit and stabilize at 10 billion people, population dynamics don't work that way.

Projected population keeps being revised every year, but this is the most recent projection from the UN:

The UN predicts that our population will peak at around 10 billion between 2075 and 2080, though I think that’s optimistic and reductionist thinking. Whatever happens with our population, the key takeaway is that the economy is about consumption. Without consumption, there is no economy.

Energy consumption

At its core, energy is the ability to move or alter the state of matter. Plants capture energy from the sun, animals consume plants (energy), some animals eat other animals (energy). All animals, including humans, need energy in the form of food. All movement requires energy. For example, the human body needs around 1800 kcal per day to maintain basic functions. Economic activity also requires energy, which is why energy consumption closely tracks GDP. The larger the population and the higher the level of consumption, the more energy is needed.

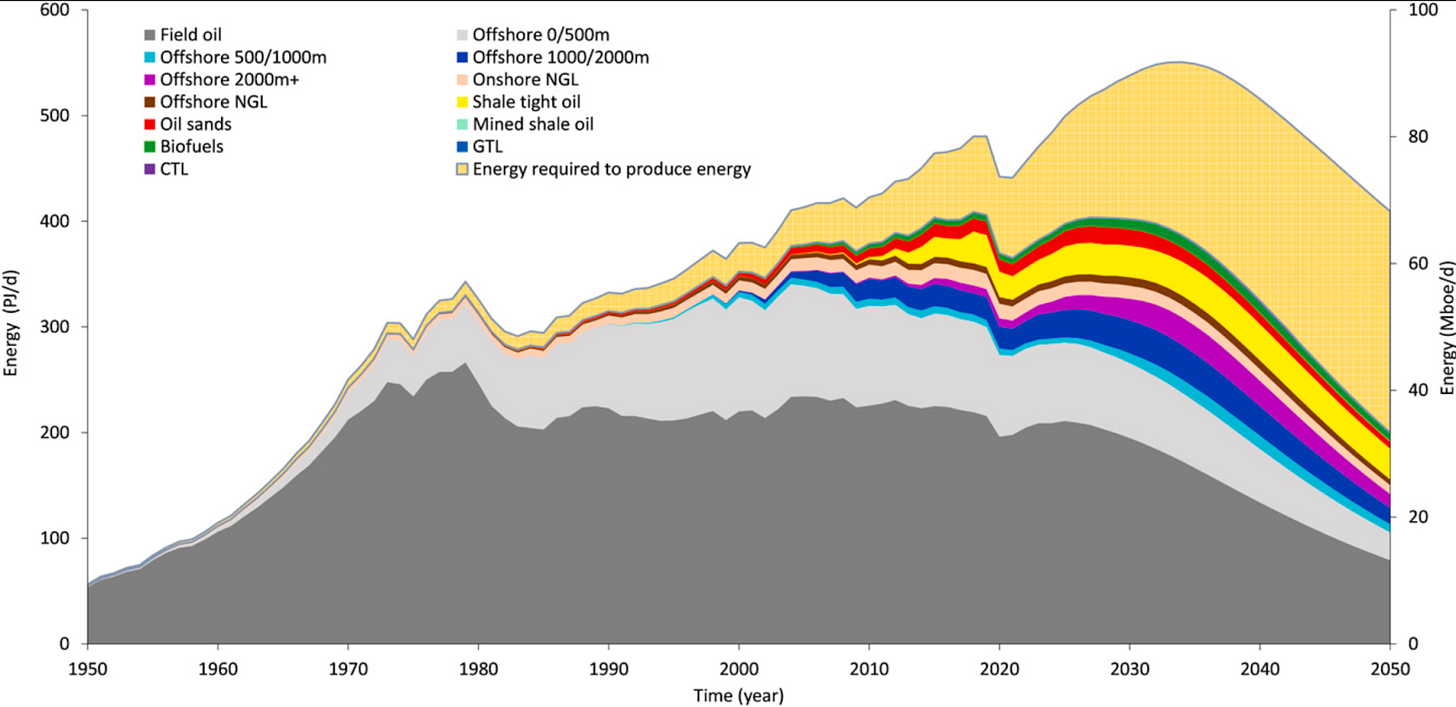

Oil, coal, and natural gas make up about 70% of the world’s primary energy. These hydrocarbons are much more energy-dense than solar or wind will ever be. They’ve been forming for millions of years, they’re finite resources, and we’re burning through them fast. Once they’re gone, they’re gone forever.

Even if emissions/climate change wasn’t an issue, we would need to replace 70% of our energy sources pretty soon to maintain our current levels of economic activity. Just to maintain the current economy is going to be very challenging, but to continue growing, we need a miracle.

Some countries claim they’ve decoupled their economies from fossil fuel use, but when you look closely, it doesn’t hold up. Take Norway for example, while their local economy might look decoupled, they still depend on energy-intensive manufacturing from other countries. They have merely outsourced production to places like China, India, and Brazil, and shifted their energy footprint elsewhere.

Fossil fuels & Peak Oil

Peak oil is the point when global oil production reaches its highest point and starts to decline. Oil is a finite resource, and as it becomes harder to extract, production slows down. This means higher prices, and not only at the gas station.

What’s in a barrel of oil?

Gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, heating oil, asphalt, plastics, packaging, lubricants, synthetic fabrics, and chemicals in things like cosmetics and fertilizers, basically, everything. Modern life relies heavily on cheap fossil fuels, and without them, our current way of life wouldn’t be possible. To keep the economy functioning, we’ll need substitutes for all these products before oil runs out or becomes too expensive to extract.

While about 50% of the world’s oil reserves are still out there, most of the low-hanging fruit has already been tapped. The remaining oil is harder and more expensive to get, meaning we’re facing higher energy costs in the future.

Renewable energy

Renewables are an attempt to save our current way of life, not the environment or nature. Renewables could play a part in softening the impact from the coming energy crunch, but they will never replace fossil fuels. A lot of things we rely on today, plastics, medicines, fertilizers, depend on oil. Renewables are actually rebuildable, meaning parts need to be replaced over time, and they require huge amounts of raw materials.

Transitioning to an electrified global economy would mean massively expanding the electrical grid, which needs enormous amounts of copper, steel, and plastics. Materials that require a lot of energy to mine and produce.

Solar panels batteries are made from minerals like lithium, cobalt, and manganese, all of which are finite and require energy-intensive mining, transportation, and shipping – all of which are powered by oil at the moment. Even recycling these materials demands a lot of energy and it’s not likely to scale fast enough or be cost-effective.

How will industries like aviation or cargo shipping transition? If they don’t, what happens to global supply chains, tourism, travel, and related sectors? It’s hard to see how we can keep growing the global economy at 2% per year during such a massive transition.

Renewable are not that environmentally friendly nor are they sustainable. Sure, they are better than fossil fuels, but that doesn’t mean they are good for the environment. It’s a dead end in the long run.

Raw materials

Global GDP and material consumption are closely linked. Everything we produce and consume requires raw materials, many of which are not renewable on human time scales. Ultimately, the planet is finite, and so are its resources. We may substitute one material for another until that, too, runs out, leading to an ongoing cycle of substitution until we hit limits.

With projections of 7x GDP growth by 2100, it’s reasonable to assume that material consumption should also rise, reaching 800 billion tonnes per year, compared to today’s 100 billion tonnes (roughly 12.5 tonnes per person). That is obviously not going to happen. It’s impossible.

So what happens when growth stops?

Most people in Western countries already have everything they need. We don’t really need more stuff (we need less). Just maintaining what we have should be enough. With a small decrease in population and GDP, we’d still be fine.

However, we need to consider the implications of demographic shifts. To simplify, if everyone is retired and no one is working, society can’t function. We still need farmers, nurses, doctors, teachers, plumbers, construction workers, and others to keep things going. In most developed countries, we’re heading towards a future with a large retired population demanding pensions, a shrinking working-age population, and an even smaller younger population. This is already a problem in many countries, like Japan, South Korea and China, and will be soon in most of the developing world.

The demographic pyramid is changing, and it’s time to rethink many of our assumptions.

Governments are trying to solve this with immigration, but that strategy has backfired in many places, with more and more voters calling for less immigration. It’s also a temporary solution to a much larger problem that isn’t going away.

Techno-optimists will claim that automation and AI will help fill the gaps in productivity as the working population declines, but they will not solve the other side, which is consumption. Robots don’t eat or consume goods. Will machines be buying Big Macs, iPhones and Teslas? Of course not.

But it gets even worse

Let’s say we somehow solve the energy problem and smoothly transition without any major economic disruptions. While I think this is pretty much impossible, I’ll play along for a minute. Let’s also assume the population keeps growing and we maintain steady growth for at least the next 75 years. Plus, let’s assume raw materials are either unlimited or we can recycle and substitute them efficiently to meet rising demand.

In that case, could growth continue? Technically, yes. But, these assumptions are way off from what’s actually realistic. If they were true, and most people seem to believe so, we could keep growing.

But here’s the thing we need to seriously think about, something that’s hardly ever discussed in business schools (at least not when I was there):

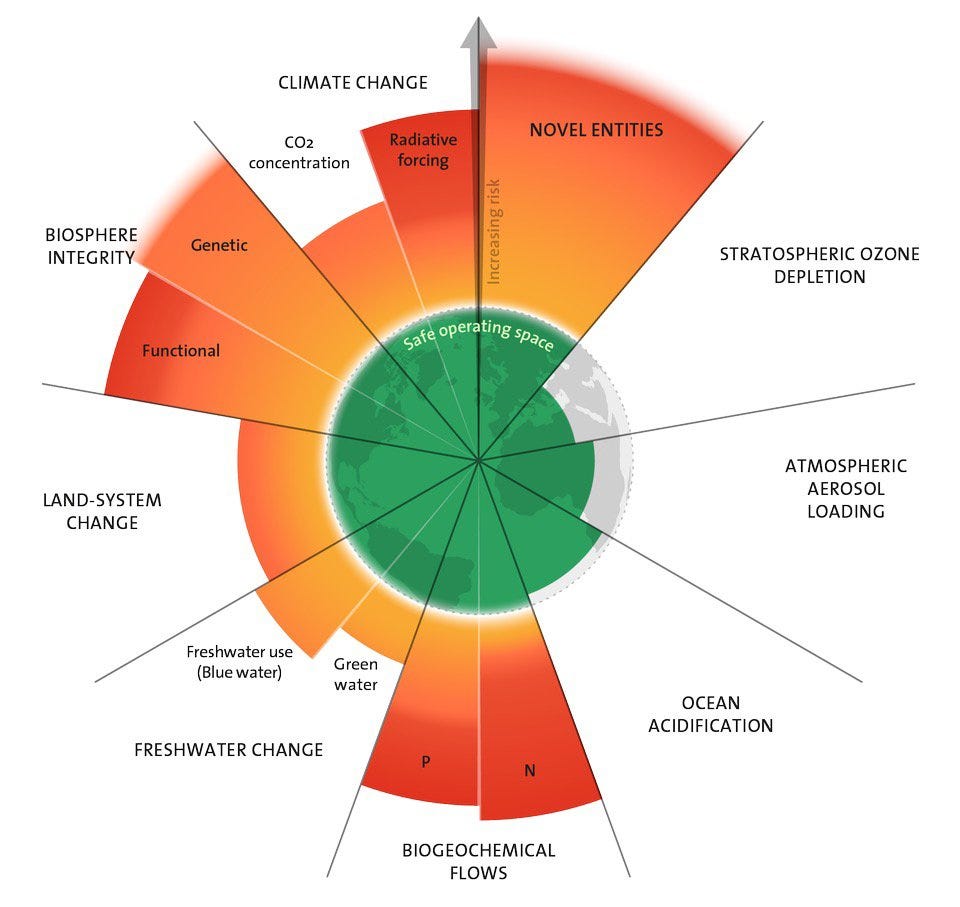

Overshooting planetary boundaries

We’re all products of nature and evolution, totally dependent on Earth’s systems to survive. The air we breathe, the food we eat, and the water we drink all come from hundreds of millions of years of evolution shaping the planet's ecosystems.

The planet has a limit, its carrying capacity. Basically, there’s only so much that Earth’s resources and ecosystems can support.

We’re using up resources faster than they can be replenished, and polluting ecosystems faster than they can handle our waste. Instead of living sustainably off Earth’s resources, we’re burning through the capital. We’re depleting things like topsoil (which is critical for growing food), fresh water, forests, metals, minerals, and fossil fuels.

We are breaking the planetary boundaries at breakneck speed.

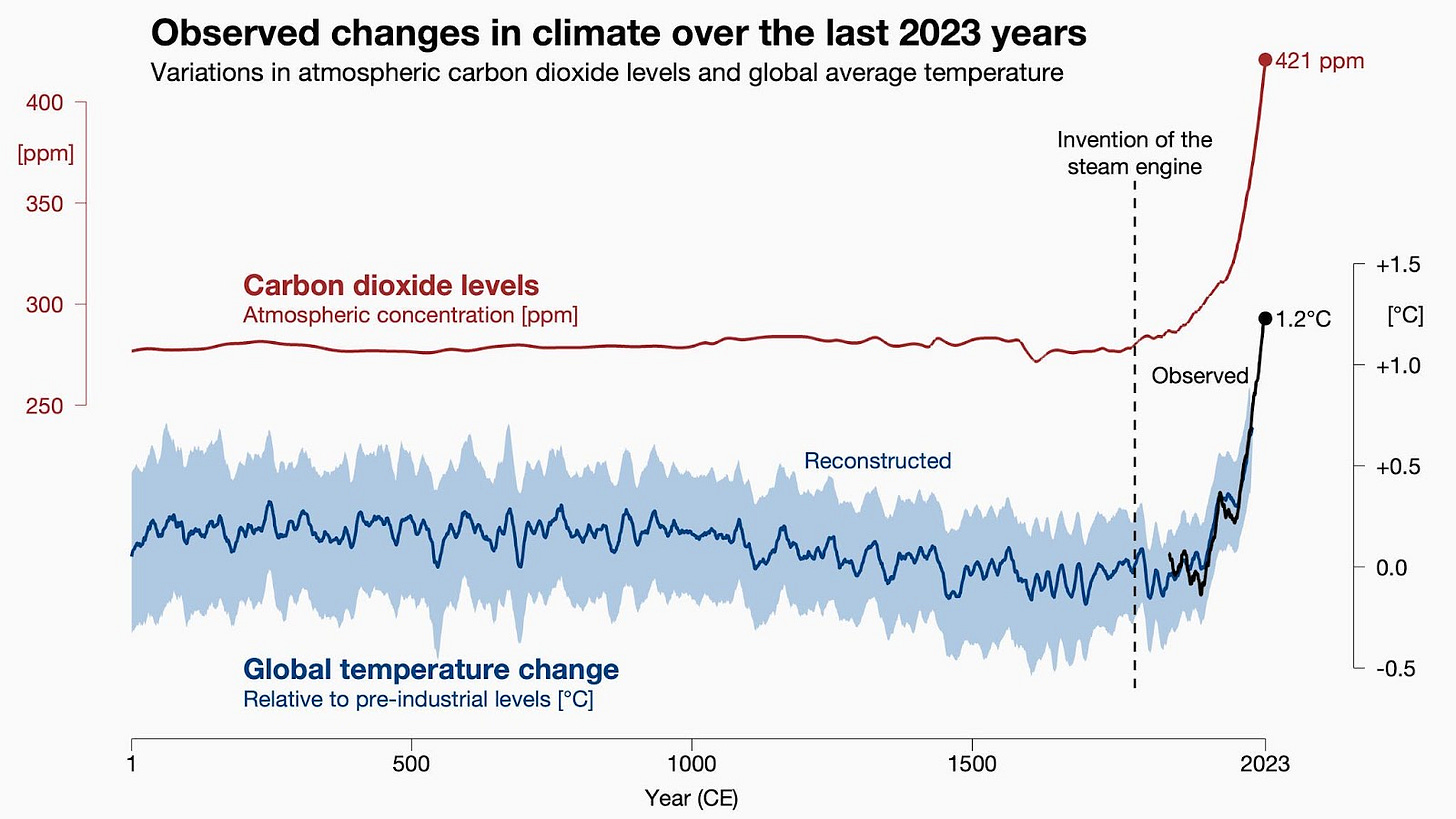

One big sign of us going beyond the planet's limits is climate change. It’s a direct result of pollution from greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane (CH4). These gases trap heat in the atmosphere, which warms the air and the oceans. You can see a historical overview of CO2 levels here.

The below graph shows CO2 levels and average temperatures over the past 2,000 years. Since we started burning fossil fuels in the 1800s, CO2 levels have shot up, and global temperatures have followed. This is physics, not up for debate. We’re currently in an out-of-control acceleration, heading into totally unknown territory. You can read my article on climate change here.

Impact on the future

For the past 10,000 years, we’ve been lucky enough to live in a pretty stable climate, called the Holocene epoch. The stable climate gave us everything we needed; predictable rainfall and temperatures, an environment that made agriculture possible. With an excess of food, we were able to build societies, grow populations, and eventually create technology, infrastructure, and global supply chains.

But since the 1800’s, our population and consumption per capita exploded and we started using up resources like crazy; depleting topsoil, draining aquifers, and polluting the planet without considering the long-term effects. The very systems that allowed us to grow, the climate and ecosystems, are collapsing.

Climate change is happening faster than ever, and it’s clear that our world has changed. We're dealing with record-breaking temperatures, extreme weather, and environmental destruction, all of it happening faster than we can keep up with. The stability that helped us build modernity is now gone, and we’re looking at the very real risk of a systemic collapse.

With CO2 levels at 424 ppm and average temperatures already over 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, we’re heading straight for a climate disaster.

The years 2023 and 2024 have seen many records broken and we can expect things to get much worse, and at an accelerated pace. Even the acceleration is accelerating.

We’re going to see more frequent and intense weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, floods, wildfires, and powerful storms that can level cities. Each disaster causes physical damage, and the response will likely be to rebuild in the same areas, even though they will get hit again, often with even more severity. Insurance companies will eventually stop covering these losses (or go bankrupt trying to cover them), leading to mass migrations, social chaos, and conflicts.

If key crop-growing regions fail, it’s almost certain we will have food shortages and famines, and that could happen within the next couple of decades. If the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) slows, Northern Europe would face a mini ice age in just a few decades. We’ve probably already triggered several tipping points that are speeding up climate change, making many places uninhabitable within this century.

As we push past the planet’s limits and burn through cheap energy resources, prices will go up, and our quality of life will take a hit.

It shouldn’t be surprising that we’re seeing more right-wing extremism, this tends to happen when times get tough (think Italy and Germany in the 1920s and 1930s). As people deal with economic struggles, many are looking for someone to blame.

There’s this idea that we can somehow go back to the "good old days" of abundance, like the whole “Make America Great Again” movement. People think we can just turn back time to when things felt easier, the economy was thriving, and resources seemed endless. But those days are long gone. Wishing for the past won’t fix anything. It's time to face the reality of the situation.

There’s a lot more to discuss about climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, and all the other effects, but I’ll save that for another time.

This was all predicted a long time ago, but most people didn’t want to hear it. Club of Rome - Limits to Growth (1972) business as usual projection:

Economic growth got us into this mess, and it’s time to face facts: it can’t keep going forever. The whole idea that we can grow non-stop on a planet with finite resources is simply impossible. We need to ditch the growth mindset and wake up to an ecological reality. Renewables? They’re mostly about saving our current way of life, not fixing the planet or the systems that keep everything alive. What we need is a global wake-up call, because growth has hit its limit, and we have to learn to live within the Earth’s boundaries.

I called several financial advisors asking how I should invest $1m for 40 years (hypothetically, but they didn't know that). I verbally explained the trends for the future, based on your excellent articles, and asked them to advise me a suitable investment portfolio that will deliver returns. Every single one of them laughed me off the phone and told me I was delusional. I am in no way surprised that 99% of the Global North assumes the trajectory of the last 75 years will continue for the next 75 years. And quite frankly, at this point, we deserve everything coming for us.

"Renewables are an attempt to save our current way of life, not the environment or nature." This should be on billboards everywhere.